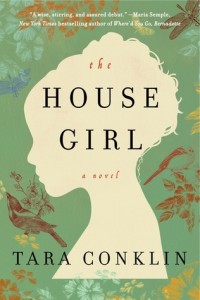

I checked out a copy of The House Girl, by Tara Conklin, from my local library.

I checked out a copy of The House Girl, by Tara Conklin, from my local library.

Description from Goodreads:

Two remarkable women, separated by more than a century, whose lives unexpectedly intertwine . . .

2004: Lina Sparrow is an ambitious young lawyer working on a historic class-action lawsuit seeking reparations for the descendants of American slaves.

1852: Josephine is a seventeen-year-old house slave who tends to the mistress of a Virginia tobacco farm—an aspiring artist named Lu Anne Bell.

It is through her father, renowned artist Oscar Sparrow, that Lina discovers a controversy rocking the art world: art historians now suspect that the revered paintings of Lu Anne Bell, an antebellum artist known for her humanizing portraits of the slaves who worked her Virginia tobacco farm, were actually the work of her house slave, Josephine.

A descendant of Josephine’s would be the per-fect face for the lawsuit—if Lina can find one. But nothing is known about Josephine’s fate following Lu Anne Bell’s death in 1852. In piecing together Josephine’s story, Lina embarks on a journey that will lead her to question her own life, including the full story of her mother’s mysterious death twenty years before.

Alternating between antebellum Virginia and modern-day New York, this searing tale of art and history, love and secrets explores what it means to repair a wrong, and asks whether truth can be more important than justice.

Review:

I have to preface this review by noting that I read this book for my book club and it is not a book I would have picked up on my own. As a result, I can’t say I enjoyed reading it. I felt satisfied by the ending (thank goodness) but I basically had to force myself to read it. This, however, is more a symptom of not being a preferred story type for me than actual quality of the book or writing.

Having said all that, there were a few things that I think, even outside my general dislike of depressing fiction, are worth mention and critique. First, while I understand Josephine is/was an artist and sees/saw things through an artists eye, the overly descriptive writing got on my nerves. Even in people’s hand written letters to one another, they were describing refracted light and how the moon shimmered, etc. It was just too much for me.

Secondly, the interminable lists, there are soooo many lists of things in the book, some of them very long. Yes, some of this served a purpose, but god, so boring to read. Third, there are a number of unbelievable coincidences that occur. Yes, some of them could be that information wasn’t hidden so much as no one had thought to look for it, but still Lina’s investigation was too easy.

Fourth, why did Lina have to romantically consider almost every man she encountered? You don’t see this with male characters. Fifth, the resolution of the mother…just no; that’s all I’ll say on that.

I did very much appreciate that there was no apology for, dressing up or hiding the horrors of slavery. Nor was it ever gratuitously shown. We didn’t need to see a man whipped to death or a woman raped to know those things were happening. The inhumanity of the establishment came through quite clearly, as did some people’s blindness to it and other’s struggles with living with it but feeling helpless to change it, even when they wanted to.

My final assessment is that this is what it is, a thought provoking, ‘book club’ sort of book. Does anyone read these just for enjoyment? No one I know.